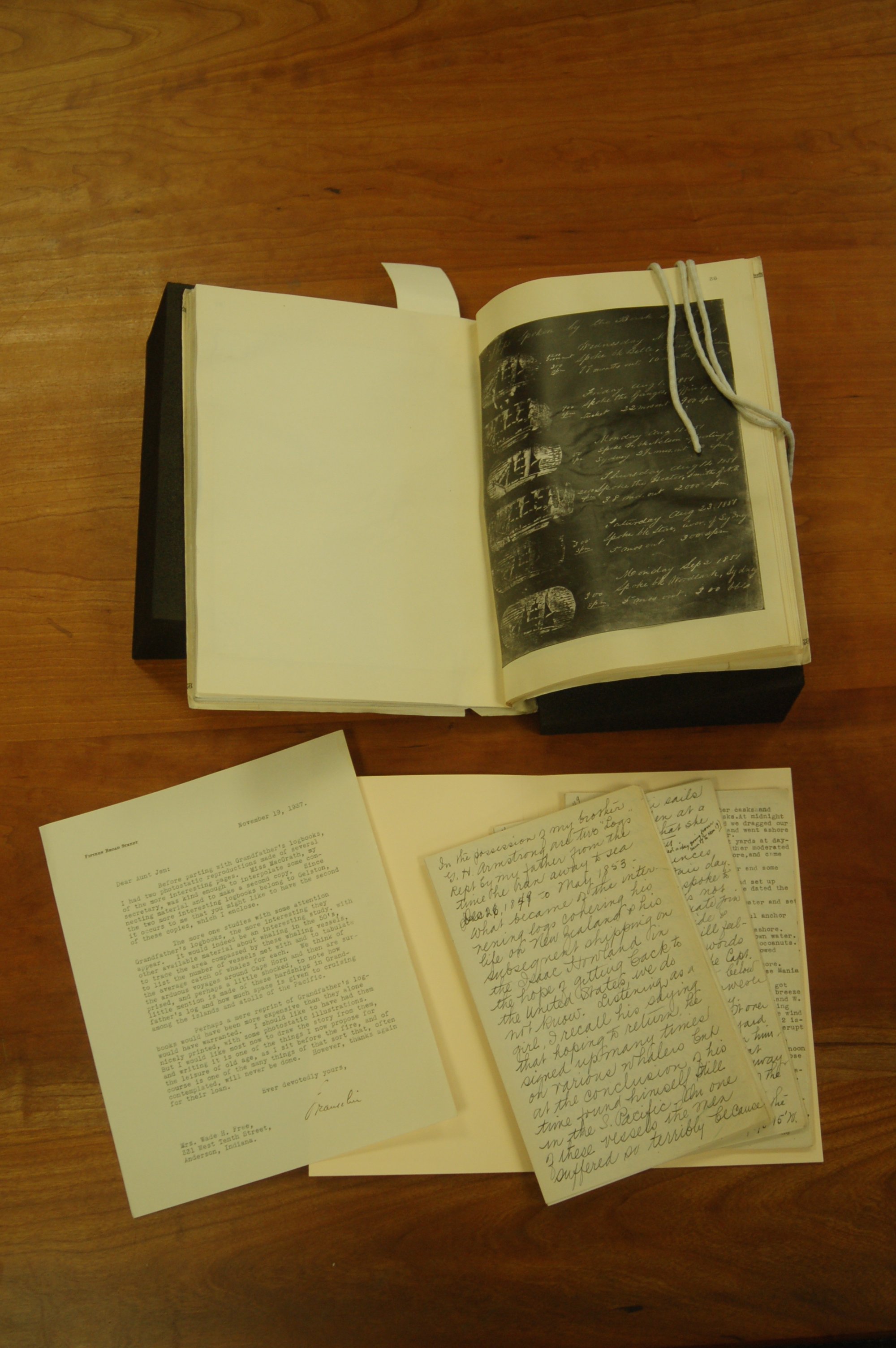

Logbooks of R.W.Armstrong courtesy of NBWM, photo by Alexander Brash

Map by R.W. Armstrong, photo by Alexander Brash

Autobiography by R.W. Armstrong, photo by Alexander Brash

FINDING THE MANUSCRIPT

While still a grad student, I called home one day to tell my parents about a whale watching trip off Cape Cod, and was astounded when my mother said, “You know, Alex, we have a whaler in our family history.” More than surprised, I was aghast. This seemed so anachronistic. Busy with my own life that day, and for years after, I brushed off the remark, and she let the matter drop.

Year later, working hard as the Chief Park Ranger in New York City, my mother again brought up the subject of the whaler.

“You know, there’s a map,” she said.

“That’s great, Mom,” I replied.

She pressed on, asserting there were more tangibles. Not only a map, but a manuscript, she said. “He’s your ancestor,” she noted with a “harrumph.” A bit vague on the details, Mom said nothing about where this manuscript was, only that the “whaler” had written about his time at sea. It still seemed abstract to me. I imagined this manuscript was, at best, a lengthy, illegible letter. More years went by.

At last I retired, and soon took the opportunity to engage in a number of generational chores with my mother, now ninety-years old; reviewing family photo albums, cemetery plots, and the like. The story of the “whaler” re-emerged in this endeavor. Indomitable, my mother again urged me to “read what I have.” So, at last, thirty-two years after I had first heard of the whaler, I acquiesced and one spring day asked to read his tale. She then slowly pulled herself up from her armchair and somewhat painfully went back to her bedroom’s closet. After a few minutes she called out, “Alex, you come do this. Pull that trunk out from back there.”

Tucked in the back of her closet, stashed under her venerable collection of dresses and skirts, was a large black leather trunk. Bound with brass hinges and corners, the dried leather was cracked, scuffed, and dinged up from years of wear. Inside the trunk was the treasure trove of her world before marriage; her family’s relics, mementos, and artifacts. Her baby shoes, white satin with pink ribbons and tiny as could be, lay on top. Beneath were her father’s WWI paraphernalia, complete with a compass, an architect’s triangle, maps, and posters. In another corner of the trunk, beneath a handful of small lead toy soldiers and a miniature train set, was a manila folder. Inside was a thick sheath of startling black pages against which bright white lettering lept out. The manuscript’s pages were akin to the dark purple mimeographed pages from my grade school days, the ones that stained my fingertips. It turned out that in 1937 my grandfather used a new-fangled photostatic machine in his office to make a complete copy of the whaler’s handwritten manuscript. Bright and clear in its antipodal presentation, the white script against the black pages made for easy reading. There was also a map of the South Pacific in the same white-on-black presentation.